A Conspectus of Tony Buzan’s “Use Your Head”

Tony Buzan’s book, “Use Your Head”, is addressed to students who need to learn how to learn. It is also an effective manual of preparation for report‐writing.

Buzan breaks the task down to three main skills: Reading, Remembering, and Note‐Making.

Reading

The eyes have to pause to take in the printed material. Therefore the eyes stop and start repeatedly as you read. Slow readers also “back‐skip”. In other words, they read the same words, sentences and paragraphs more than once.

Reading will be much faster if the jumps are longer and if more is taken in each time the eyes stop. This means taking in several words at a time. Buzan says that this is not only possible, but also easier, and results in less fatigue and better understanding.

To avoid “back‐skipping” and to build the habit of making bigger jumps, Buzan recommends that readers lead the eyes with a finger or other pointer and that readers practise taking in more words at each stop (called a “fixation”). Here are some quotes from the book:

“If eyes moved over print in the smooth manner . . . they would be able to take in nothing, because the eye can see things clearly only when it can ‘hold them still’. If an object is still, the eye must be still in order to see it . . .

“Relating all this to reading, it is obvious that if the eyes are going to take in words, and if the words are still, the eyes will have to pause on each word before moving on. Rather than moving in smooth lines . . . the eyes in fact move in a series of stops and quick jumps.

“The jumps themselves are so quick as to take almost no time, but the fixations can take anywhere from 1⁄4 to 11⁄2 seconds. A person who normally reads one word at a time – and who skips back over words and letters – is forced, by the simple mathematics of his eye movements, into reading speeds which are often well below 100 wpm (words per minute) and which mean that he will not be able to understand

much of what he reads, nor be able to read much.

“It might seem at first glance that the slow reader is doomed, but the problem can be solved, and in more than one way:

- Skipping back over words can be eliminated, as 90 per cent of back‐skipping is based on fear and is unnecessary for understanding . . .

- The time for each fixation can be reduced to approach the 1⁄4 second minimum – the reader need not fear that this is too short a time, for his eye is able to register as many as five words in one‐hundredth of a second.

- The size of the fixation can be expanded to take in as many as three to five words at a time.

“This solution might at first seem impossible if it is true that the mind deals with one word at a time. In fact the mind can equally well fixate on groups of words, which is better in nearly all ways: When we read a sentence we do not read it for the individual

meaning of each word, but for the meaning of the phrases in which the words are contained.

“The slower reader has to do more mental work than the faster reader because he has to add the meaning of each word to the meaning of each following word.

“Another advantage for the faster reader is that his eyes will be doing less physical work on each page. Rather than having as many as 500 fixations tightly focused per page as does the slow reader, he will have as few as 100 fixations per page, each one of which is less muscularly fatiguing.

“Yet another advantage is that the rhythm and flow of the faster reader will carry him comfortably through the meaning, whereas the slow reader, because of his stopping and starting, jerky approach, will be far more likely to become bored, to lose

concentration, to mentally drift away and to lose the meaning of what he is reading.

“It can be seen from this that a number of the commonly held beliefs about faster readers are false:

- Words must be read one at a time: Wrong. Because of our ability to fixate and because we read for meaning rather than for single words.

- Reading faster than 500 wpm is impossible: Wrong. Because the fact that we can take in as many as six words per fixation and the fact that we can make four fixations a second means that speeds of 1000 wpm are perfectly feasible.

- The faster reader is not able to appreciate: Wrong. Because the faster reader will be understanding more of the meaning of what he reads, will be concentrating on the material more, and will have considerably more time to go back over areas of special interest and importance to him.

- Higher speeds give lower concentration: Wrong. Because the faster we go the more impetus we gather and the more we concentrate.

- Average reading speeds are natural and therefore the best: Wrong. Because average reading speeds are not natural. They are speeds produced by an incomplete initial training in reading, combined with an inadequate knowledge of how the eye and the brain work at the various speeds possible.

“Apart from the general advice given above, some readers may be able to benefit

from the following . . .

- Visual aid techniques: When children learn how to read they often point their finger to the words they are reading. We have traditionally regarded this as a fault and have told them to take their fingers off the page. It is now realised that it is we and not the children who are at fault. Instead of insisting that they remove their fingers we should ask them to move their fingers faster . . .

- Expanded focus: In conjunction with visual aid techniques, the reader can practise taking in more than one line at a time. This is certainly not physically impossible and is especially useful on light material or for overviewing and previewing. It will also improve normal reading speeds. It is very important always to use a visual guide during this kind of reading, as without it the eye will tend to wander . . .

- High speed perception: This exercise involves turning pages as fast as possible attempting to see as many words per page as possible. This form of training will increase the ability to take in large groups of words per fixation, will be applicable to overviewing and previewing techniques, and will condition the mind to much more rapid and efficient general reading practices . . .

- Motivational practice: Most reading is done at a relaxed and almost lackadaisical pace, a fact of which many speed reading courses have taken advantage. Students are given various exercises and tasks, and it is suggested to them that after each exercise their speed will increase by 10‐20 wpm. And so it does, often by as much as 100 per cent over the duration of the lessons. The increase, however, is often due not to the exercises, but to the fact that the student’s motivation has been eked out bit by bit during the course . . .

- Metronome training: A metronome, which is usually used for keeping musical rhythm, can be most useful for both reading and high speed reading practices. If you set it at a reasonable pace, each beat can indicate a single sweep for your visual aid. In this way a steady and smooth rhythm can be maintained and the usual slowdown that occurs after a little while can be avoided. Once the most comfortable rhythm has been found, your reading speed can be improved by occasionally adding an extra beat per minute.

Remembering

Tony Buzan looks at the learning period, and after.

During the learning period (which could be reading, or a class, lecture, or workshop) he says that students remember more from the beginning and the end, with a dip in the middle. Therefore, he says, breaks should be taken every 20‐40 minutes (making more ‘beginnings’ and ‘ends’).

After the learning period, according to the research quoted by Buzan, knowledge tails off to almost nothing unless there is systematic review, or revision. It does not have to be extended on each occasion. Little and often is the best way.

Just these simple techniques of taking breaks and doing frequent small reviews will increase your retention of learnt material. Buzan also describes special memory techniques. These all seem to rely on associating things together in imaginative ways, an idea which Buzan picks up again in his note‐making section.

Note‐Making

Buzan’s ‘mind‐map’ technique is not so just a way of making notes. It is even more useful as a way of organising material for output, such as a report or an article.

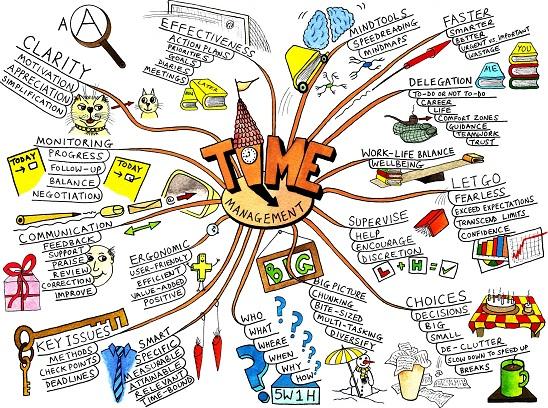

A Buzan “Mind‐Map”

Buzan argues that conventional written students’ notes are linear, whereas the material is always ‘multi‐ordinate’, meaning that each word or concept connects in many possible ways, which cannot be shown in a list or serial form.

Instead of starting at the top left‐hand corner, the mind‐mapper starts in the middle. A mind‐map is the ‘big picture’. It is the forest, not just the trees. It is a ‘helicopter view’ of the topic. In Marxist terms, it is the ‘concrete’ view of the ‘abstract’ parts. It should be dialectical. It is ‘organic’, and not eclectic. It is always a one‐page thing.

Here are some instructions for a mind‐map:

- Survey the materials to be studied; find the major topics.

- Use paper turned sideways, any good sized paper will do, A4 is suitable.

- Put the title of the major topic in the centre of the page.

- Enclose this title in some shape, but a picture is best.

- Survey the material again to find the main sub‐topics.

- Write a title for each sub‐topic on a line which radiates out from the centre topic.

- Survey again to find any subsidiary topics still not covered.

- Put branching lines from the sub‐topic line to represent the subsidiary topics.

- Give a title to each of these last drawn lines.

- At the end of the final lines write in any details that are essential to the topic.

Then it lists ‘Additional Aids’, as follows:

- Use abbreviations as often as possible, develop your own personal shorthand.

- Colour‐code branch lines to highlight hierarchies.

- Outline each sub‐topic with a different colour. This defines its outlines, limits, contents and close relationships.

- Use coloured arrows to link parts of your notes to show relationships.

- Pictures aid memory, so devise them for yourself.

The Buzan Organic Study Method

The Browse

“Before doing anything else, it is essential to ‘browse’ or look through the entire book or periodical you are about to study. The browse should be done in the way you would look through a book you were considering buying in a bookshop, or in the way you would look through a book you were considering taking out from the library. In other words casually, but rather rapidly, flipping through the pages, getting the general ‘feel’ of the book, observing the organisation and structure, the level of difficulty, the proportion of diagrams and illustrations to text, the location of any results, summaries and conclusions sections etc. . . .

Time and Amount

“The first thing to do when sitting down to study a text book is to decide on the period of time to be devoted to it. Having done this, decide what amount to cover in the time allocated . . .

“In study, making a decision about Time and Amount gives us immediate chronological and volume terrain, as well as an end point or goal. This has the added advantage of enabling the proper linkages to be made rather than encouraging a wandering off in

more disconnected ways . . .

“A further advantage of making these decisions at the outset is that the underlying fear of the unknown is avoided. If a large study book is plunged into with no planning, the reader will be continually oppressed by the number of pages he eventually has to complete. Each time he sits down he will be aware that he still has a ‘few hundred pages to go’ and will be studying with this as a constant and real background threat. If, on the other hand, he has selected a reasonable number of pages for the time he is going to study, he will be reading with the knowledge that the task he has set himself is easy and can certainly be completed . . .

“There are still further reasons for making these time and amount decisions which are concerned with the distribution of the reader’s effort as time goes on. “Imagine that you have decided to study for two hours and that the first half‐an‐hour has been pretty difficult, although you have been making some progress. At this point in time you find that understanding begins to improve and that your progress seems to be getting better and faster.

“Would you pat yourself on the back and take a break?

“Or would you decide to keep the new and better rhythm going by studying for a while until you began to lose the new impetus?

“Ninety per cent of people asked those questions would carry on. Of those who would take a break, only a few would recommend the same thing to anyone else!

“And yet surprisingly the best answer is to take a break. The reason for this can be seen by referring back to the discussion in the chapter on Memory (see above – DT) and the amount that is recalled from a period of learning. Despite the fact that

understanding may be continually high, the recall of that understanding will be getting worse if the mind is not given a break . . . It is essential that any time period for studying be broken down into 20‐40 minute sections with small rests in between.

“To assist even further, do a quick review of what you have read and a preview of what you are about to read at the beginning and end of each study period . . .

Noting of Knowledge on the Subject

“Having decided on the amounts to be covered, next jot down as much as you know on the subject as fast as you can. (2‐5 minutes). Notes should be in key words and creative pattern form (mind map).

Asking questions – Defining Goals

“Having established the current state of knowledge on the subject, it is advisable to decide what you want from the book. This involves defining the questions you want answered during the reading. The questions should be asked in the context of goals aimed for and should, like the noting of knowledge, be done in key word and mind map form . . . (2‐5 minutes).

Study Overview

“One of the interesting facts about people using study books is that most, when given a new text, start reading on page one. It is not advisable to start reading a new study text on the first page . . .

“What is essential in a reasonable approach to study texts, especially difficult ones, is to get a good idea of what’s in them before plodding on into a learning catastrophe . . .

“What this means in a study context is that you should scour the book for all the material not included in the regular body of the print, using your visual guide as you do so. Areas of the book to be covered in your overview include:

conclusions

indents

glossaries

back cover

index

tables

table of contents

marginal notes

results

summaries

illustrations

capitalised words

photographs

bibliography

subheadings

dates

italics

graphs

footnotes

acknowledgements

statistics

Preview

“During the preview, concentration should be directed to the beginnings and ends of paragraphs, sections, chapters, and even whole texts, because information tends to be concentrated at the beginnings and ends of written material.

“If you are studying a short academic paper or a complex study book, the Summary Results and Conclusion sections should always be read first. These sections often include exactly those essences of information that you are searching for, enabling you to grasp that essence without having to wade through a lot of time‐wasting material.

“The value of this section cannot be overemphasised. A case in point is that of a student taught at Oxford who had spent four months struggling through a 500‐page tome on psychology. By the time he had reached page 450 he was beginning to despair because the amount of information he was ‘holding on to’ as he tried to get to the end was becoming too much – was literally beginning to drown in the information just before reaching his goal.

“It transpired that he had been reading straight through the book, and even though he was nearing the end, did not know what the last chapter was about. It was a complete summary of the book! He read the section and estimated that had he done so at the beginning he would have saved himself approximately 70 hours in reading time, 20

hours in note‐taking time, and a few hundred hours of worrying. Books are commodities like everything else in bourgeois society. Authors are compelled to pad up their writing to the required length to make a saleable book.

Difficult Sections

“Moving on from a difficult area releases the tension and mental floundering that often accompanies the traditional approach.

“’Jumping over’ a stumbling block usually enables the reader to go back to it later on with more information from the ‘other side’. The block itself is seldom essential for the understanding of that which follows it.

Review

“In this stage simply fill in all those areas as yet incomplete, and reconsider those sections marked as noteworthy. In most cases it will be found that not much more than 70 per cent of that initially considered relevant will finally be used. Then complete your mind map notes.”

Tony Buzan’s web site is at: http://www.tonybuzan.com/