Contributed by Steve Lambert and Andrew Boyd

Common Uses

To get important information into the right hands.

Leafleting is the bread-and-butter of many campaigns. It’s also annoying and ineffective, for the most part. How many times have you taken a leaflet just because you forgot to pull your hand back in time, only to throw it in the next available trash can? Or you’re actually interested and stick it in your pocket, but then you never get around to reading it because it’s a block of tiny, indecipherable text? Well, if that’s what a committed, world-caring person like you does, just imagine what happens to all the leaflets you give out to harried career-jockeys as they rush to or from work.

In a word, if you’re doing standard leafleting, you’re wasting everybody’s time. What you need is advanced leafleting.

In advanced leafleting, we acknowledge that if you’re going to hand out leaflets like a robot, you might as well have a robot hand them out. Yes, an actual leafleting robot. In 1998, the Institute for Applied Autonomy built “Little Brother,” a small, intentionally cute, 1950s-style metal robot to be a pamphleteer. In their tests, strangers avoided a human pamphleteer, but would go out of their way to take literature from the robot.

Make it fun. Make it unusual. Make it memorable. Don’t just hand out leaflets. Climb up on some guy’s shoulders and hand out leaflets from there, as one of the authors of this piece did as a student organizer. (He also tried the same tactic hitchhiking, with less stellar results.) The shareholder heading into a meeting is more likely to take, read and remember the custom message inside the fortune cookie you just handed her than a rectangle of paper packed with text.

Using theater and costumes to leaflet can also be effective. In the 1980s, activists opposed to U.S. military intervention in Central America dressed up as waiters and carried maps of Central America on serving trays, with little green plastic toy soldiers glued to the map. They would go up to people in the street and say, “Excuse me, sir, did you order this war?” When the “no” response invariably followed, they would present an itemized bill outlining the costs: “Well, you paid for it!” Even if the person they addressed didn’t take the leaflet, they’d get the message.

The point is, leafleting is not a bad tactic. It’s still a good way to tell passersby what you’re marching for, why you’re making so much noise on a street corner or why you’re setting police cars on fire. But people are more likely to take your leaflet, read it, and remember what it’s all about if you deliver it with flair. Or ice cream.

Key Principle at work

Kill them with kindness

Nuff said. Pissing people off won’t do your cause any favors, so don’t piss people off. Disarm with charm, and maybe your audience will let their guard down long enough to hear what you have to say.

Layout

Making your material look good is not a waste. Material that looks good will be read by many more people. The waste is to lose readers because of not making your text look good. So here are some ways to control the look of your output:

International page size standards Just to give you an idea of what paper sizes are available. You will mostly use A3 and A4 and A5 and some others for posters.

White space

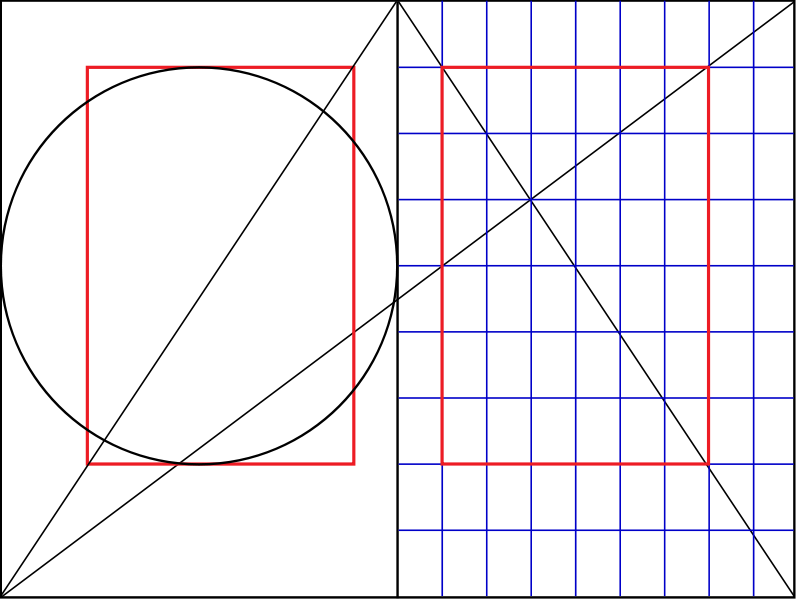

If at all possible, surround your print with white space. See the above illustration for an idea of the classic look of book pages. White space makes your material readable. The Canons of Page Construction have been well known for centuries and typographers and book designers still use their guidance today.

Bold, Italic, Underline, and BLOCK CAPITALS

Be careful with Block Capitals. They can make your material look as if you are shouting. But otherwise, all of these devices can help you to create a hierarchy of meaning that will help your readers to understand you better.

Fonts

There are many. They are either serif (like “Times”), or they are sans‐serif (like “Calibri”).

Justify

Justify is used for columns. Columns are used for newspaper articles, and magazines. Columns allow more words on the page.

Numbering (footer)

Always number documents that have more than two pages. The most versatile numbering format is the one that goes at the bottom and in the middle. It works for left‐hand (verso) and right‐hand (recto) pages equally well.

Headlines

Try to keep headlines on one line. Less is more. Five words is a lot, for a headline.

Logos

Use logos when you can. They create an impression of authenticity.

Break up slabs

Use all kinds of ways to break up large slabs of text, so as to give your readers resting points, and landmarks in the text.

Fliers (Flyers) and Leaflets

These

are handed out free, as advertising. Usually they only have text on one

side. Sometimes they are miniature versions of a poster. Most political

fliers are A5 (half an A4) in size.

Fliers need to project the message that they are supposed to convey, very simply and clearly. People who take fliers do not, on average, spend more than a few seconds looking at them. Very few of them will keep the flier or look at it twice. Therefore the main information must be the most prominent information.

If the flier is to advertise an event, then the main information is Date, Time and Venue. The nature of the event comes after these in importance, even if it is put at the top of the flier. But of course it must also be there.

As with posters, it is important to avoid the kind of “clutter” that obscures the simplicity of the message.

Text in sentences and paragraphs is unlikely to be read. Text in slogan form, and as announcement is what goes on fliers. In other words, less is more. The graphics, layout and illustration should support and not compete with the text.

Logos can be used, but what gets most attention on any page is always the same thing: A human face or a human figure. In text, what gets most attention is names of people. Polychrome is not necessary in a flier design, just as it is not necessary in a poster.

Pamphlets

A

pamphlet is a text publication. It is usually like an essay, or what is

sometimes called a tract. It is similar to writing for periodicals like

theoretical magazines, or as part of a book. The difference from these

is that the pamphlet is an occasional and not a regular publication, and

it is shorter than a book.

A pamphlet might typically be A5 in size, several thousand words in length, and anything from 4 to 32 pages, or sometimes even more than that. Pamphlets are often printed professionally. Sometimes they have a cover, sometimes not.

Pamphlets have a long history in politics. The one of the most famous pamphleteers in the English language is Tom Paine. The 1848 Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels is a pamphlet, maybe the most successful one ever.

A pamphlet is always an option when an occasional response or publication is needed.

Copy Shops, Distribution and Markup

The

cost of printers has come down massively in recent years. Even laser

printers can be bought for $100. A colour laser printer from $200.

These are perfectly good for printing A4 and A5 booklets and flyers. You

can get cheaper generic toner replacements on eBay. The manufacturer’s

replacement toner is often very expensive. Don’t bother with inkjet

printers. Their inks will run if the paper gets wet. For those who don’t

have access to a laser computer printer Copy‐shops like Officeworks and

Kwik Kopy and Snap allow people access to printing on demand in urban

centres and in some small rural towns.

Copy‐shops are usually based on the use of photocopiers. These machines can print direct from an electronic file, which can be sent to the print‐shop by e‐mail, or brought to the shop on a thumb‐drive (flash drive) or on a CD, or downloaded by the shop from a web site.

Customers pay per copy. It means that they can order and get what they can afford.

Copy‐shop Agitprop

Copy‐shops

open the door for small, local organisations to get into print and

become autonomous producers of agitprop material. This may include

pamphlets, political education booklets, and publicity fliers.

Distribution and Markup

You maybe able to distribute your materials to supportive cafes, book shops, medical centres, community centres.

You may be limited to what you can pay for, and you may have to give out your material to the public free. A proportion of your output, and maybe most of it, will always be of this kind. It is one among many ways to project your agitational propaganda. This is where you have to use the principle of “Mark‐up”. In business, most commodities are “marked up” from the purchase price to the sale price by at least 50%. Sometimes the markup is 100%.

You, too, need a markup, to make the business swing. There is no such thing as “break even”. If you aim for “break even” you will lose money.

Don’t forget that the value of the material in the product was also made by labour, as much as the physical object was. So it is up to you to give value by making sure that the content is good.